Submitted by Angela Walters on Wed, 11/12/2019 - 14:53

|

As part of CDBB’s series of blogs to mark Gemini Principles: One Year On, Technology and Construction Lawyer and Sessional Academic at Queensland University of Technology, Australia, Brydon Wang, considers the role of principles in making smart cities and digital twins trustworthy.

|

Can we utilise the Gemini Principles and other complimentary principles to make our smart cities and their digital twins more trustworthy?

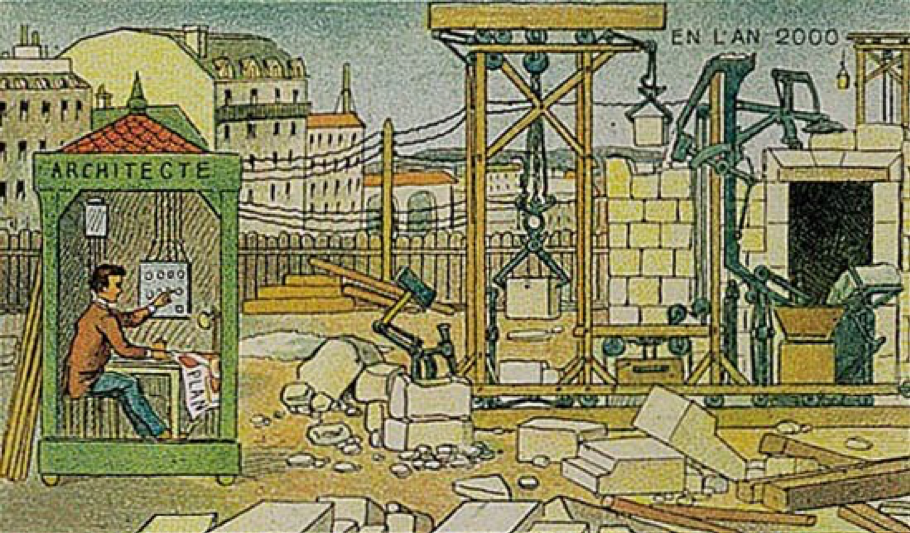

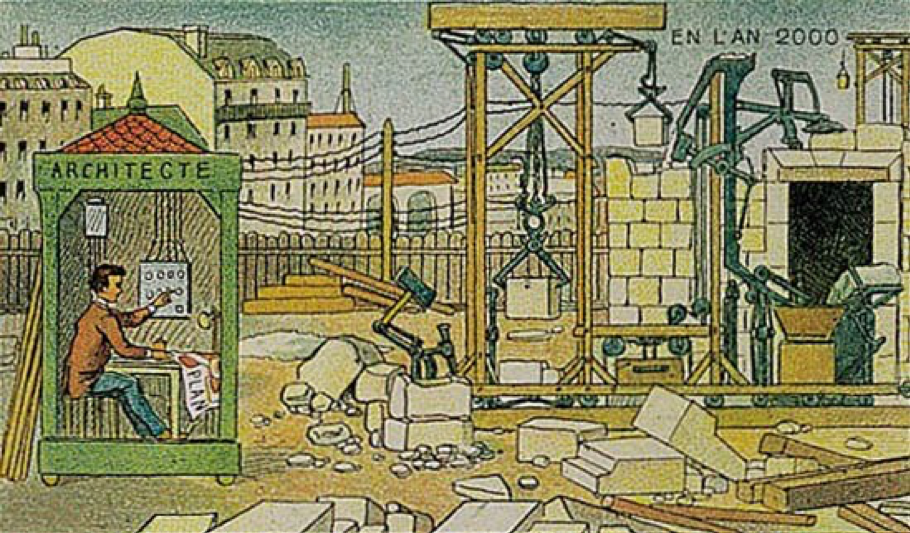

I am fond of this particular French illustration from 1910 predicting what life would be like in the year 2000. It depicts an architect in a little booth on a construction site, pushing levers to run a robotic arm that controls the building process. This reality has come to fruition – we now have various automated means of pre-fabricating building components and carrying out construction activities onsite.

The machine superintendent

We’re now trying to automate other aspects of the infrastructure delivery process. My current research looks at how we draw sensor data from our built environment (‘dataveillance’) and the way we utilise this data to make trusted decisions. Currently, a person would have to physically attend to make observations about a site, building, or an infrastructure asset. But with a proliferation of sensors embedded in our built environment, we’re able to automate this data acquisition process, and model what is happening on the ground to share information among project participants. Digital twins and other common data environments reflect our progress in this area.

We’re also using the data acquired from our built environment to automate decision-making on construction projects. These include technologies that seek to automate the scheduling process and construction programming; 3D scanners and Radio-frequency Identification (RFID) technology to accurately determine the progress of works; and the automated performance of legal obligations through smart contracts.

The risk of seamless technology offerings

However, these technologies seek to utilise urban data from sensors in the city to produce a seamless dataveillance-to-decision-output process path. For example, in 2018 Google’s sister company in the urban innovation space, Sidewalk Labs, unveiled the operating platform ‘Coord’. The platform sought to create a ‘seamless trip experience for cities’ (Sidewalk Labs, 2018) by drawing from ride-share apps, parking meters, and other sources of traffic information to allow decision-makers to shape policy and regulate traffic. As Richard Budel, CIO of Huawei has said, the goal of digital twins is to bring about the automation of decision-making processes in the city.

This makes a difference; the deployment of digital twins shifts our practice of city-making from one that is informed by data to one that is driven by dataveillance. This collapses the task of collecting data to inform decisions into a larger process where dataveillance seamlessly becomes the actual practice of decision-making within the city. Given that digital systems and the urban data they rely on play an increasing role in decision-making in the construction process and infrastructure delivery, we must consider how trustworthy these systems are.

But what is trust in the context of decision-making around a smart city?

My on-site experience as an architect and contract administrator and subsequent role as a technology and construction lawyer has allowed me to appreciate how complex the problem of trust is on construction projects. A key aspect of this trust problem is the improper exercise of discretion by superintendents who play the part of a trusted intermediary on construction contracts. With the automation of contract administration processes, we’re given the opportunity to consider how to build our systems to be more trustworthy.

In their 1995 paper on organisational trust, Mayer, Davis and Schoorman observed three factors of perceived trustworthiness: ability – how competent a potential recipient of trust (or ‘trustee’) is; integrity – whether the actions of the trustee demonstrates a willingness to comply with the norms and value systems in place (ie, that there is ‘value congruence’); and benevolence – whether the trustee means the person who is trusting (or ‘trustor’) well.

Much of my work as a lawyer was guiding clients in how to respond to the component of ‘integrity’. We advised clients on how they could comply with their contractual obligations, and beyond the contract, the legislative framework around their sector of activity. Similarly, a digital twin must demonstrate integrity in supporting the existing norms and fulfil the commercial drivers seeking to establish the technology. But what are these norms and commercial drivers? Given that the technology of digital twins is still maturing, we are witnessing the early formulation of principles and attempts to guide the industry to a standard for this developing technology. The Gemini Principles are one such attempt at developing the industry standard and norms in relation to the collection of data to create digital twins. Similarly, the IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems (Ethically Aligned Design or ‘EAD1e’) is another example of how industry participants are seeking to establish the appropriate boundaries for the use of A/IS. These emerging principles have the potential to help shape how we prioritise the wellbeing of individuals in our use of their data within digital twins.

Utilising the Gemini Principles and other emerging principles, my research aims to consider how the formulation of these norms affects how the functional brief for this technology is created, and what values are being promulgated. Potentially, how these principles are developed and articulated may also help technology companies, policy makers and other industry participants demonstrate that they have designed these systems to be benevolent towards the urban occupant.

Contact: Brydon Wang, Technology and Construction Lawyer and Sessional Academic at Queensland University of Technology, Australia